Sculpture News at SculptSite.com

Sculpture News at SculptSite.com

Ursula von Rydingsvard Sculpture |

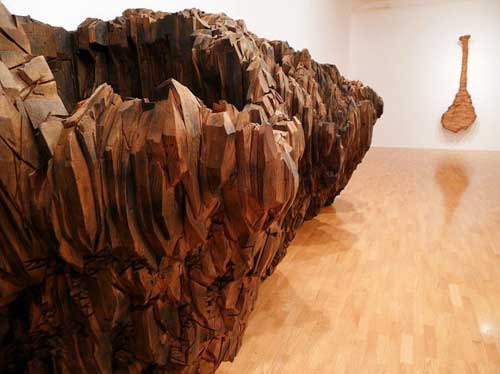

| Cleveland.com By Steven Litt, The Plain Dealer Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland says farewell to old home with spectacular Ursula von Rydingsvard sculpture showIt doesn't get any better than this. Then again, knowing the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, it very well could. MOCA is closing out its 21-year residency in the former Cleveland Play House complex in Midtown with a spectacular farewell exhibition on the sculpture of Ursula von Rydingsvard, a major contemporary figure, before moving to its new home in University Circle in 2012. The show, organized by the Sculpture Center in New York's Long Island City with independent curator Helaine Posner, opened Friday. It's a top-notch experience of the kind MOCA has regularly turned out in recent years, and it sends the message that the museum's audience should expect just as much, if not more, in the future. Von Rydingsvard, 69, is a German-born, New York-based artist admired around the world for dramatic structures made of glue-laminated planks of milled cedar, which she cuts and stains to resemble rocky cliffs, volcanic outcrops, primitive vessels or inscrutable monuments from a lost civilization. The artist is best known for colossal outdoor sculptures installed in sculpture parks, corporate campuses and museum grounds around the world. Given their scale and rewarding complexity, it's unusual to see more than one of her works at a time. The revelation of the MOCA show is that it provides a long, deep look at her indoor sculptures, which are diminutive only in relation to the larger outdoor pieces. The exhibition comprises nine large pieces or installations and several works on paper, which have turned MOCA into a virtual one-woman museum. Von Rydingsvard's sculptures encompass vast swaths of art history while remaining utterly personal and immediately identifiable. They seem eerily primitive yet utterly contemporary. Despite their immensity, they're made up of countless small gestures -- produced by the circular saws she and her assistants use to carve the wood -- like brush strokes in a painting. Also, despite their bigness, von Rydingsvard's sculptures have a remarkable intimacy. They bowl you over and then pull you in for a hug. Perhaps most of all, the sculptures appeal to inchoate memories of nature or emotional states and may trigger a wide variety of associations among different viewers. A large piece, titled "Droga," sprawls across a section of MOCA's polished oak floor like a curling wave, frozen in motion. Viewed from one angle, it's a tunnel. Viewed from the opposite end, the work opens up and appears to unfurl and spill its interior across the floor, like a part of a mountain sinking into the sea. The floor, in this context, becomes a watery surface from which the piece emerges. You think you're in an art gallery, but you could be on a volcanic shoreline in Iceland, where hot magma is pouring into the frigid Atlantic. In MOCA's rotunda gallery, at the far back end of the exhibit, von Rydingsvard has installed a recent piece, titled "Halo With a Straight Line." Like "Droga," it evokes a host of associations. It's a towering, U-shaped structure that resembles a throne, a mountain cliff, a slice of a desert canyon hollowed out by the furious power of fast-running water. On its outer flanks, the piece has bulges and pockets, like naturally occurring baptismal fonts, perhaps, or reservoirs created by the dripping of mineral-rich waters in deep caves. You can examine the work from a distance, walk all around it, or step right inside its curling mass to feel its dark embrace around you and smell the warm, woody odor it exhales. "Ocean Floor," a piece from 1996, is a giant bowl, which appears to have been hewn out of layers of sedimentary rock. Its outer rim is notched and adorned with pouches made from blackened cow intestines, which have been stitched around muslin bags filled with peat moss and molded into mysterious shapes resembling oversize lead fishing weights. Or perhaps instead of functioning as ballast, the pouches could be buoys, intended to lift the giant bowl on a rising tide. Either way, looking at the piece, you feel the presence of powerful natural forces -- wind and waves, frost and fire. "It's important to me to have many metaphors," the artist said at MOCA last week, taking a break after installing the exhibition. "I don't want to be too easily pinned down." Sculptor hopes to convey humanity Tall and slim, and dressed head to toe in form-fitting black, von Rydingsvard looked both athletic and ethereal during her visit to MOCA, much as she does in photographs of herself at work in her studio. "I'm immersed in black," she said. "You open my closet, and it's all you see." Born in Deensen, Germany, in 1942, von Rydingsvard was the fifth of seven children born to a pair of peasant farmers. Her father, a Polish-speaking Urkrainian, was conscripted by the Nazis as a slave laborer. She recalls living from the end of World War II to 1950 in nine refugee camps for displaced Poles, in which her parents fought to keep her and her siblings alive. Despite enduring prolonged periods of privation, von Rydingsvard said that her early years are "not key to my work." She acknowledged that her sculpture "has a lot of vulnerability," but said that what's she's after is "humanity, energy and hopefulness." In 1950, von Rydingsvard's family resettled in Plainville, Conn., where the artist graduated from high school before leaving for college, first at the University of New Hampshire and later at the University of Miami. In Florida, she met and married a medical student, Milton von Rydingsvard, whose name she has kept even though the marriage ended in divorce in 1973. That same year, she moved to New York and spent two years earning a master-of-fine-arts degree at Columbia University. By the end of her studies, von Rydingsvard had become acquainted with milled cedar, which became her sculptural medium of choice. Over the years, she has developed a working method in which she orders lengths of cedar in bulk, with no fewer than 22 growth rings to the inch. Anything less, she said, and the wood would splinter, fragment and fly off when cut with a saw, producing messy, unpredictable edges. She buys 3,000 circular, tungsten-steel saw blades at a time and uses the saws with the safety guards retracted so she can "nibble" at the cedar or lunge at it, making what she calls "plunge cuts." Making an individual sculpture involves making thousands of cuts. She then applies powdered graphite and has her assistants scour the material into the wood. This blackens and enriches the wood surfaces and gives her pieces a look of having been aged, perhaps for centuries, and perhaps by being exposed to fire or having been buried in the earth. The rugged surfaces, improvisational methods and large scale of von Rydingsvard's sculptures bring to mind associations with Abstract Expressionist painting of the 1950s, in which painters such as Clyfford Still or Franz Kline used repeated slashing gestures to build up craggy, silhouetted images that evoked primal landscapes and overpowering emotional states. Show bodes well for MOCA's future The sculptor's attachment to sinewy, irregular surfaces also recalls the way in which Chinese and Japanese scholar-artists have for centuries collected limestone rocks and boulders eroded into fantastic shapes by running water. Then, too, von Rydingsvard's deep attachment to wood evokes the medieval northern European obsession with forests as dwelling places of mysterious beings such as the "Wild Man," or the "Hairy Man," who lived outside the structures of society. The artist welcomes all such interpretations, although she would rather not have her work framed too closely by any of them. The Abstract Expressionists mean less to her than the Minimalist sculptors of the 1960s and '70s, she said. Among painters, Giotto, the early Renaissance Italian master, is a favorite. Most of all, she said, her work has been a search to find something that's uniquely hers. "You don't come out of nothing," she said, "but I feel that I came out of something that was mine, and the more mine it is, the better." Anyone seeing the show will be immediately impressed with the strength, clarity and distinctiveness of von Rydingsvard's work. It's impossible to mistake it for anything else in contemporary art. More than anything, von Rydingsvard's sculpture radiates an old masterly sense of having been made by hand. In a high-tech age in which more and more artists are using mechanical or photo-based techniques as if to erase a sense of personal touch, von Rydingsvard endows her work with a deep sense of humanity. By heavily and brutally working with wood, she fashions deeply evocative abstract forms capable of rewarding repeated viewings throughout the show's long run through March, making it an excellent choice for MOCA's swan song in Midtown. Apart from its purely artistic impact, the show is a declaration that when MOCA moves to its new home in University Circle in October 2012, it will have the highest ambitions. No one should expect anything less. Established in a University Circle storefront in 1968, MOCA has spent the past 43 years thoroughly exploring fresh artistic terrain the more conservative Cleveland Museum of Art chose to ignore or downplay until recent decades. MOCA's new home, an architecturally dramatic building designed by architect Farshid Moussavi of London, will occupy a highly visible spot at the point of the urban triangle formed by Euclid Avenue and Mayfield Road. Steel framing is already up. The von Rydingsvard exhibition, coming on the eve of this move, raises the very highest hopes for MOCA's future. It also indicates that a brilliant next phase in the life of a vitally important Cleveland institution is just about ready to begin. |

Sculptress Ursula von Rydingsvard, there is only one! Her work is reflective of life's erosion - reminds me of the Grand Canyon. Life seems to be an erosion in time, all so natural. Cleveland deserves an exhibit of this proportion. An absolutely wonderful read by Steven Litt of The Plain Dealer! Go to Cleveland, even if you have a memory problem, you will never forget a sculpture exhibition of this magnitude by Ursula von Rydingsvard. |

"Halo With a Straight Line" by Ursula von Rydingsvard |

"Krasavica II" by Ursula von Rydingsvard |

"Ocean Floor" by Ursula von Rydingsvard |

Ursula von Rydingsvard |

More Sculpture News ....

Submit your SCULPTURE NEWS.

It's easy, just send us an e-mail

(click on Submit News in the left menu) with your pertinent information along with images, we'll take care of the rest. Sculpture makes our world a much better place in so many ways!

SculptSite.com, along with Sculptors and their creative genius all helping to bring the beauty and message of Sculpture to a hurried world.