Sculpture News at SculptSite.com

Sculpture News at SculptSite.com

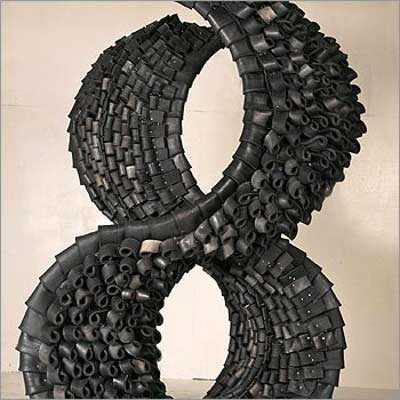

Chakaia Booker Sculpture |

| The Boston Globe by Sebastian Smee Big, black sculptures bristling with ambition have colonized the entire DeCordova Sculpture Park + Museum in Lincoln. They’re upstairs, downstairs, inside and out, and even on the roof. Made from recycled black rubber tires, they’re by Chakaia Booker, an African-American artist who lives and works in New York and Allentown, Pa. Booker, 57, is one of the most interesting sculptors around right now. Her concerns, in this day of multimedia installations, can seem a mite traditional: She makes freestanding sculptures, wall reliefs, and pieces perched on pedestals, all of them built around armatures of steel or wood. Ostensibly abstract, their forms allude poetically to the human body and to architecture. Yet her best works manage to infuse these concerns, so deeply rooted in art history, with terrific zest, unearthing dynamic new possibilities of expression. The material itself - recycled tires and their inner tubes, spliced, stretched, twisted, knotted, and otherwise reshaped - is at the heart of Booker’s success. In its proliferating textures, these tires express a metamorphic freedom one would never have suspected from such abject, obdurate material. (Try picking up a car tire. Now try cutting through its structural bands of steel and tearing it into pieces. Booker does this daily; I’m assured she has good tools.) But if the surface textures of Booker’s sculptures are endlessly surprising, suggesting everything from animal armor to palm fronds and feathers, the forms have a tendency toward symmetry that can feel rigid and unyielding. Sometimes there’s expressive power in this very rigidity - something austere, implacable, and foreboding. But at other times the interest palls. Too many of Booker’s works, I found, are structured around boxy, predictable shapes, reducing the astonishing textures and shifting black, glossy, and matte tones of the tires to empty ornament. I much preferred the works that played fast and loose with form - the ones that seemed to spill out of themselves, playing havoc with the distinction between structure and surface, embracing asymmetry and, with it, a kind of pressurized psychological release. All this comes through most strongly in Booker’s smaller works. Her wall piece "Twist of Fate," for instance, is little more than a sculptural sketch - an insouciantly tied bow that resembles a piece of three-dimensional Zen calligraphy. But its loops and arabesques set up their own internal rhymes and pressures. It works. Another small wall piece, "Crossed Vagina," imitates the shape of Picasso bull’s head constructed, with typical wizardry, from a bicycle seat and handlebars. The yielding but muscular texture of Booker’s rubber tires feels like a witty retort to Picasso’s hard, impermeable materials. Booker - and it’s a sign of her ambition - has an eye on a wide array of sculptors, from the Athenian who created the Belvedere Torso (evoked in an impressive work suggesting thwarted strength called "Untitled (Male Torso That Left His Path)" to contemporaries like Tara Donovan (who also makes inventive use of discarded materials). Her fondness for pendulous parts, sometimes extending to the floor in languid loops and spirals, calls to mind the hanging sculptures made from rope and latex by the late Eva Hesse. Her love of found materials fastidiously arranged and colored black recalls the all-black assemblages of Louise Nevelson. And her penchant for creating a sense of hidden and mysterious force cloaked in wrapping might also suggest such artists as Christo and Jeanne-Claude and Jackie Winsor. But perhaps the strongest links - at least within Western sculpture - are with Richard Serra and Robert Morris, who not only used comparable industrial materials like latex and felt, but also linked their sculptural production with varieties of performance. Booker, for her part, has long delighted in adorning herself with spliced and sewn rubber, set off by colorful fabrics and elaborate headwear. A series of photos at the DeCordova attests to this theatrical, vamping strain, and it also points to the profound connections between Booker’s sculptures and the rich African and African-American traditions of hair design, patterned textiles, and body decoration. Again and again, the surfaces of these tough rubber sculptures suggest the softness and warmth of shorn hair, while the patterns of the tire treads loosely evoke tribal body paint and African hair designs. All this jostles around in your mind as you wander from piece to piece. The connections spark excitement. But surface effects are just that: In sculpture, everything still depends on the three-dimensional presence of the forms as a whole. Unfortunately, quite a few of Booker’s bigger, more ambitious pieces are let down by her dependence on symmetry and otherwise lifeless, prepackaged forms. "Shhh," which evokes African masks or headgear on a giant scale, was not nearly as imposing as its size demanded, while the two smaller totemic forms on the rooftop terrace, "Hybrid" and "Meeting Ends," were neat without really requiring a deeper response. The same problem applied to "Take Out," an empty rectangular frame; "Gridlock," twinned vertical S shapes; and "(Wrench) (Wench) II." Far more compelling - in fact unforgettable - is Booker’s most celebrated work, "It’s So Hard to Be Green." This massive wall piece attracted positive attention when it appeared in the 2000 Whitney Biennial. It resembles a gargantuan painting or tapestry out of which spills all the viscera of postindustrial civilization. Either that, or simply a magnified patch of unruly black hair. Take your pick. But the best thing about it - the detail that brings it to life and sloughs off the potentially dulling effect of its underlying symmetry - is the diagonal streak of glossy rubber extending from the top left corner. It evokes the shininess of scar tissue, accentuating the sculpture’s associations with both belligerent menace and concealed damage. Booker’s sculptures work when they elicit just these sort of indefinite but immediate and instinctive responses. There are more than enough examples to make this exhibition worth visiting. I’ve no doubt that it will be remembered as one of the most compelling solo shows in the Boston area this year. |

Sebastian Smee has brought the work of Chakaia Booker to a very understandable level. There doesn't seem to be a whole lot one could add, except to say "get over and see this exhibit sooner rather than later." I don't think you will ever forget it if you do! |

"It’s So Hard to Be Green" is in the exhibit "Chakaia Booker: In and Out." The massive wall piece is made of rubber tire and wood. |

Anonymity 2007 |

Twist of Fate |

More Sculpture News ....

Submit your SCULPTURE NEWS.

It's easy, just send us an e-mail

(click on Submit News in the left menu) with your pertinent information along with images, we'll take care of the rest. Sculpture makes our world a much better place in so many ways!

SculptSite.com, along with Sculptors and their creative genius all helping to bring the beauty and message of Sculpture to a hurried world.